This paper will be presented at the 2018 Participatory Design Conference in Hasselt & Genk, Belgium. The paper discusses an approach that combines participatory and speculative design practices to enable non-reformist reform. It explores how we might challenge the limits of the status quo by using speculative design’s intention of provocation, while engaging in a participatory process that includes the people who are most impacted by current oppressive systems. In a case study based in Ferguson, MO, community members imagined futures where neighborhoods are kept safe without policing. Speculative props were designed to materialize community members’ visions and to provoke conversation around our utopias and their negative implications. This work confronts challenges around public participation, collaborative visioning and the long process of enacting radical systemic change.

1. Introduction

As the theme of this year’s conference reminds us, participatory design has always been about the democratic ideal to “emphasize the right to maintain a different opinion than those in power, to forward opposing positions, and to build knowledge on an alternative basis to support a different view” [1]. It is a difficult task to develop and explore this different opinion when everything around us supports a singular dominant narrative. For example, the project in this paper presents the question: What if we could keep neighborhoods safe without policing? People often respond to this with denial. The professional structures of policing we know today are relatively new, yet it is difficult for us to imagine alternatives. As Alain Badiou says, “The power in place doesn’t ask us to be convinced that it does everything very well […] but to be convinced that it’s the only thing possible.” Without other options in sight, it is difficult to avoid “the prevailing powers’ control over possibles” [2].

Our inability to imagine beyond our current political structure is a central challenge in the work of non-reformist reform. This idea rejects reformist reform, or incremental change within existing systems. Instead, non-reformist reform re-imagines problematic systems from their ideological roots [3]. This idea has been used before to describe the goals of participatory design [4]. Angela Davis and others who advocate for the abolition of the prison industrial complex call for non-reformist reform today, explaining that the U.S. criminal justice system is rooted in oppression and control of oppressed groups, and that any reform that happens within it will simply strengthen that oppression [5]. Instead, we must envision alternative systems that involve a fundamental shift in power structure. This requires us to loosen our grip on the status quo, and to imagine radical alternatives. It asks us to pivot and build a different future rather than reforming our current systems.

This paper explores how participatory and speculative design practices can be used together to enable non-reformist reform by provoking debate about alternative options at a systems level. Design is used both to collaboratively “re-design” the socio-material infrastructure of policing itself, and more instrumentally, to design speculative props that make alternative visions tangible.

2. Using Speculative Design

Speculative design is useful for non-reformist reform because of its intention to provoke rather than to propose. Projects do this by untethering themselves from designing a proposal to be implemented. While typical design projects are defined by the boundaries of the systems around us in order to generate concepts that can exist within those systems, speculative design projects are removed from this criteria and allowed to question the limits of the system itself.

By striving for provocation, we can generate the radically different systemic possibilities that challenge what we think is possible. As an example, we can look at the case studies shared by Knutz, Lenskjold, and Markussen as they discuss how fiction can be used in participatory design [6]. Although these projects use other concepts from speculative design, they are still framed to produce a proposal to be implemented, rather than a provocation, which does not question the underlying assumptions of the existing system. In one example, paper dolls are used to learn about what types of prosthetic limbs best suit Cambodian children’s needs in different environments. This does not question why the children need prosthetic legs or help us to imagine a future in which children do not lose their legs. Projects like these examples are important to improve day-to-day life within our current circumstance. However, in pursuit of non-reformist reform and a foundational shift of underlying values and beliefs, we may be well served by using speculative design to produce questions and provocations.

While speculative design is framed to provoke debate and inspire a diverse range of possibilities, it often does not succeed because of who is invited to participate in it. The field is criticized for being homogenous and privileged, failing to confront the difficult social problems that projects expose [7, 8]. Similar to the problems of classic utopianism [9], speculative designers attempt to open critiques of emerging technologies or social power structures, but do so from their own privileged worldviews. While designers may collaborate with professional experts on scientific or technological trends, it is rare that they work with people who are most impacted by the issues projects confront. In the end, speculative projects typically appear as static images or artifacts on display, prioritizing the aesthetic vision rather than enabling a collaborative process of imagination.

As Disalvo says, it is not only a problematic mistake to avoid the politics of our imagined speculations, but also a missed opportunity to use speculative practices as a tool for political debate [8]. Thankfully, there are speculative design practices that challenge this trend, as well as a history of speculative arts that engage with the politics of imagining futures from an oppressed position. The Extrapolation Factory attempts to democratize the futuring process [10], Deepa Butoliya asks us to acknowledge the imagination of non-western and subaltern perspectives [11], and Elizabeth Chin performs an antiracist design anthropology [12]. We can also look to movements like afrofuturism and feminist utopianism [9].

3. Case study: Futures of Public Safety

It has been increasingly well-acknowledged that the U.S. criminal justice system is rooted in a history of racial oppression. The New Jim Crow [13] charts the history of racial politics, showing how white supremacy was invented as a way to divide and conquer the lower classes, and how our current policing, court and prison systems emerged in pursuit of social control. All of this leaves us to wonder who the criminal justice system is built to “protect and serve”.

Ferguson is the site of nationally broadcast protests in 2014 after Darren Wilson, a white police officer, shot and killed Michael Brown, a young black man. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) responded to the protests by investigating the police department and publishing a report that called Ferguson court and policing practices unconstitutional. This led to a consent decree between the DOJ and the City of Ferguson that required heavy policy reform in the city. At the demand of protestors, the Neighborhood Policing Steering Committee (NPSC) was created in 2016 to give community members a voice in the reform.

While this process has opened possibilities for reform, it has largely maintained a “reformist”, rather than non-reformist, stance. The official legal process has called for specific policy changes in recruiting, training, and community engagement within the police department. The consent decree asks us to reform policing practices while maintaining its overall structure. Even throughout the protest community, the conversation centers around self-defense rather than re-imagining the fundamental structure of public safety systems.

Yet, there is a desire to imagine alternatives. Growing out of my participation in the NPSC, the Futures of Public Safety project strives to address the deep foundational roots of our cultural ideology that criminalizes people of color and responds to crime with violence rather than healing. The goal of this project is to collaboratively imagine alternative social structures and explore “different opinion[s] than those in power.” It combines speculative and participatory design practices to enable a process of non-reformist reform.

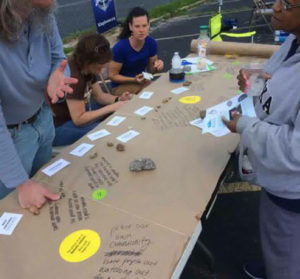

Figure 1: Re-imagining policing table at NPSC block party

After working with the NPSC to develop one speculative vision of a future where we keep communities safe without policing, the group decided to set up a table at an upcoming block party to involve more community members in similar creative thinking ( Fig. 1*). We asked Ferguson residents to imagine how a different system of public safety might respond to specific scenarios: witnessing domestic violence, having a car stolen, or driving over the speed limit. Fig. 2* maps the different ideas we heard, combined with NPSC survey results and other information about the mindsets of Ferguson residents. This map was displayed at another street fair, hosted by the Center for Social Empowerment in Ferguson, where participants could roll a dice and describe the future they landed in.

Figure 2: Diagram displayed at street fair event. Participants rolled a dice and described what the world they landed in would be like. ©Alix Gerber

Based on these conversations, three futures emerged, from government led to community led: the Future of Public Service, the Future of Hearts and Minds, and the Future of Grassroots Cooperation. Each world replaces policing with an alternative form of public safety. In the Future of Hearts and Minds, for example, local religious organizations manage public safety through an approach based in morality and self-control. Residents look out for each other and direct lost souls to religious leaders, viewing immorality not as a personal failing but an external spirit that must be expelled.

For each of these worlds, I built a scene ( Fig. 3*) that included a backdrop and props from the world it depicted. Through an exhibition atWashington University and an event at the Center for Social Empowerment in Ferguson, participants were invited to occupy the scenes, take on the role of someone responsible for public safety, and consider which elements of the world they want to bring back to the present, and which they hoped would never happen. Making visions of the future tangible in this way builds on the use of prototyping to “establish a shared (concrete) language across disciplines” [14]. This shared language helps us transcend worldview across race, class, and privilege. When a concept has been explored visually and tangibly, each person can use their own mindset to interpret the same thing. Then, we can define our disagreements more clearly and debate issues more explicitly.

Figure 3: Future of Hearts and Minds scene ©Alix Gerber

Each artifact invites a critical analysis of its scene and attempts to represent the complex web of positive and negative elements of the ideology. For example, the Future of Public Service replaces police with social workers who ensure that each person has access to the public services they need in order to prevent harmful behavior. In this scene, viewers may sit at a desk and take on the persona of a case manager. On the computer screen, the Risk Profile shows the client’s risk for anti-social behavior, drug abuse and violence ( Fig. 4*). Viewers also see a list of factors that influence and have been used to calculate the risk, including “few living relatives” and “adverse childhood experiences”. This visual asks viewers to consider the level of surveillance that would be required to collect this data, and also how we might respond to someone with high risk. The system views at-risk people in a beneficent way, but would we still force a level of “help” that individuals might not desire in the name of public safety?

Figure 4: Top: Profile screen from the Future of Public Service, Bottom: Protector scout badges from the Future of Grassroots Cooperation ©Alix Gerber

Ultimately, the scenes did provoke a clearer conversation about how participants envision the future. At one of the events, two active protesters shared their thoughts on the Future of Grassroots Cooperation, a vision developed based on an anarchic ideology that they often adhered to. This scene represented a world in which neighbors protect each other on a hyper-local, neighborhood block scale. A Protector Scout Vest (Fig. 4*) laid across a living room chair, with badges representing skills children might learn: mediation, community networking, and use of fire-arms, among others. The backdrop looked outside the home to a neighborhood street. Looking at the scene, the participants began to talk about their own vision in a tangible, aesthetic way: this future would be lush and green, it would have more personality. They pushed back against the Scout Vest, explaining that this represented the top-down, militaristic order they opposed. Presenting a flawed interpretation of their vision provoked a conversation that began to shed light on what they really imagined.

4. Discussion

This project has only begun to explore the possibilities of using speculative and participatory practices to strive for non-reformist reform. It attempts to do this by provoking collaborative imagination about alternative options at a systems level. This is a challenging task for multiple reasons: 1) developing futures as a public depends on public participation and investment; 2) beyond imagining alternatives as an individual, non-reformist reform depends on community debate and collaborative visioning; and 3) enacting radical systemic change is a long, multi-generational process.

While this project did successfully conduct multiple participatory events, time was often limited and the people most likely to engage were not always those most impacted. With limited time and energy, people often choose to invest in activities that will have the most short-term impact. Thus, the same disconnection from concrete impact that makes it possible to imagine radically different futures can also make it difficult to gain participants’ commitment. A lack of financial support also made it difficult to spend time organizing the public to engage in the project.

Non-reformist reform and the ideals of accommodating a plurality of voices require community debate and conversation. In this project, the designed future artifacts became a site of debate by building on the speculative design idea that visions of the future should be flawed. This way, multiple contrasting opinions can exist within the representation of one artifact. For example, the badges on the Protector Scout Vest were influenced both by one participant’s comment: “Members of the community can help people get to the root of the problem through community conversation.” and another’s reaction: “I don’t think a thief deserves death, but in the heat of the moment, he might get shot if I’m having a bad day.” Taken together, these comments begin to illustrate a world that is cooperative, emotional and lawless, valuing honest communication and also requiring firearms for protection. The Scout Vest shows this by including badges representing skills like mediation and community networking side by side with use of firearms. By incorporating multiple ideas of the future in the same artifact, people who have never spoken or met can be put in conversation with each other.

However, depending on a central designer to represent peoples’ voices involves a heavy responsibility to represent those voices authentically. For example, the Future of Hearts and Minds was inspired by the prevalence of Christian religion in how participants spoke about morality and healing from criminal behavior. With little experience or knowledge about the religious backgrounds of the participants, I built on these contributions to envision a space that emphasized a more Euro-centric vision of Christian religion, problematically erasing the aesthetic worldview of the original intention. Ideally, visions would incorporate the voices of participants themselves, including leaders from the realms in question. This happened in one instance when a Christian talk show host, Barbara Kizzie, recorded a prayer for the fictional world to display within the scene. By involving experts like Barbara, the Future of Hearts and Minds was able to incorporate more of an appropriate voice.

Critics of this project often ask, ’Beyond enabling imagination, what impact does this work have on real change?’ First, it is important to defend the act of imagining alternatives. Without this, radical reform would not be possible. At the same time, why imagine alternatives if there is no hope that they might create actual impact? As Disalvo emphasizes, “To be truly provocative is to rouse to action” [8]. Especially when we deal with issues that deeply impact many peoples’ lives every day, we cannot afford to stop here. Shifting our established infrastructure to embody the vision we have imagined is a long-term venture that can only be achieved as a national mass. Prefigurative politics provides one glimpse of how we might temporarily perform pieces of these systems in order to test them out on a smaller scale. In the context of Ferguson, the practice of participatory speculation has functioned as a layer on top of policy making and protest, activities that can put energy behind actualizing the visions that are explored through this kind of imagination.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts and the Louis D. Beaumont Visiting Assistant Professorship. Thank you to the Neighborhood Policing Steering Committee who has graciously accepted me as a member, as well as the Center for Social Empowerment for their partnership. Molly Brodsky, John Chasnoff, Reybren Fitch, Barbara Kizzie, Liz Kramer, Maya Mashkovich, Anu Samarajiva, Kaitlyn Schwalber, and Sukari Stone have all played a part in making this project a reality, in addition to the many people who suspended their disbelief and participated in imagining the future. Thank you also to the reviewers who have strengthened this paper throughout its development, including Andrea Botero and Marc Steen.

Read more at www.designradicalfutures.com

References

[1] Gro Bjerknes and Tone Bratteteig. 1994. User participation: A strategy for work life democracy?. In Proceedings of PDC’94 (PDC ’94). CPSR, 3–12.

[2] Alain Badiou and Fabien Tarby. 2013. Philosophy and the Event. Polity Press, Cambridge, UK.

[3] Andre Gorz. 1967. Strategy for Labor: A Radical Proposal. Beacon Press, Boston, MA.

[4] David Hakken and Paula Maté. 2014. The Culture Question in Participatory Design. In Proceedings of the 13th Participatory Design Conference: Short Papers, Industry Cases, Workshop Descriptions, Doctoral Consortium Papers, and Keynote Abstracts – Volume 2 (PDC ’14). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 87–91. https://doi. org/10.1145/2662155.2662197

[5] Angela Davis. 2003. Are Prisons Obsolete? Seven Stories Press, New York, NY.

[6] Eva Knutz, Tau U Lenskjold, and Thomas Markussen. 2016. Fiction as a Resource in Participatory Design. Design Research Society (2016), 1–15.

[7] Luiza Prado and Pedro Oliveira. 2014. Questioning the ’Critical’ in Speculative and Critical Design. Retrieved May 18, 2018 from https://medium.com/a-parede/ questioning-the-critical-in-speculative-critical-design-5a355cac2ca4

[8] Carl Disalvo. 2012. Spectacles and Tropes: Speculative Design and Contemporary Food Cultures. Fibreculture Journal 20 (2012), 109–22.

[9] Shaowen Bardzell. 2018. Utopias of Participation: Feminism, Design, and the Futures. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction 25, 1 (2018), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1145/3127359

[10] Chris Woebken and Elliott P. Montgomery. [n. d.]. The Extrapolation Factory. Retrieved May 18, 2018 from http://extrapolationfactory.com/

[11] Deepa Butoliya. 2018. Critical Jugaad. Retrieved May 18, 2018 from https: //primerconference.com/2018/deepa-butoliya/

[12] Elizabeth Chin. [n. d.]. Laboratory of Speculative Ethnology: Using Fiction to Explore Facts! Retrieved May 18, 2018 from https://elizabethjchin.com/portfolio/ laboratory-of-speculative-ethnology/

[13] Michelle Alexander. 2010. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. The New Press, New York, NY.

[14] Eva Brandt, Thomas Binder, and Elizabeth B.-N. Sanders. 2012. Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design. Routledge, Florence, Chapter Tools and Techniques: Ways to Engage Telling, Making and Enacting, 145–81.